Closed houses of worship served during 1918 flu pandemic

Peter Smith

Peter SmithBy Peter Smith

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

April 20, 2020

The faded, single-spaced letter from the fall of 1918 has a jolting immediacy to readers today.

“A very unusual opportunity has come to Calvary Church,” the clergy of the Episcopal congregation in Shadyside wrote to its members. “To meet the present emergency of our pandemic-stricken community, the Vestry (governing board) has tendered the use of the Parish House to the United States Military authorities. The rooms will be used as a convalescent hospital” for military trainees recovering from influenza.

The global influenza pandemic of 1918 known as the Spanish flu peaked in Pittsburgh in October and November, ultimately killing more than 4,500 people and infecting more than 60,000 throughout Allegheny County, according to historical accounts. Worldwide, it claimed at least 50 million lives, according to estimates cited by the Centers for Disease Control.

Though far deadlier than the current pandemic, the influenza competed on newspapers’ front pages with the American military’s grinding progress in World War I and a relentless campaign to buy war bonds. Yet the headlines have a familiar feel. Houses of worship were shuttered as pastors urged people to worship in their homes, and faith-based groups rallied to help those affected by the illness.

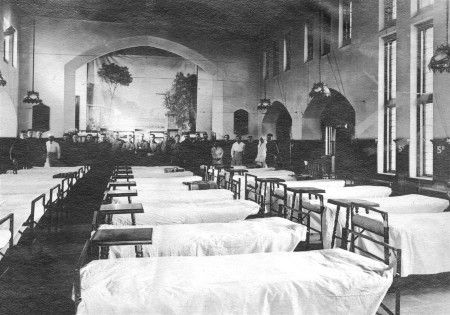

Calvary Episcopal Church, a historic congregation with an architecturally rich Gothic sanctuary, turned over its adjoining Parish House for a 60-bed hospital to serve patients who had gotten over the worst of the flu but were still regaining strength.

“Every man cared for here releases a bed in the city hospitals, where space is urgently needed for the people of our city,” wrote the Revs. Edwin Van Etten and Lewis Whittemore.

They asked for donations of “current magazines, games, good books of stories, fruit, jellies, flowers” and newspaper subscriptions for the patients. The pastors assured church members that the sanctuary itself was quarantined and would be safe when the church reopened. It had been closed along with most other houses of worship after the influenza began spreading rapidly in early October.

At first, the state closed saloons and other gathering places but left the question of churches to local officials. Church-goers that first weekend in October were likely to see a police notice at the entrance saying, “Any person having a cough or cold is not to enter this church.”

But by Oct. 7, with the influenza raging throughout the city, the mayor ordered houses of worship closed.

The archives show that Roman Catholic Bishop Regis Canevin and the Pittsburgh Council of Churches, a Protestant interdenominational group, agreed to the closures. Archives in the Jewish Chronicle newspaper indicate that synagogues also complied.

There were no livestreaming options yet, but Calvary did mail sermons, Bible readings and prayer materials to members. The Pittsburgh Council of Churches asked families to use the 11 a.m. hour on Sundays for “devotions, Bible reading and prayer” at home.

“Let us in humility and faith pray earnestly for the removal of this sickness prevailing throughout the land,” the council ministers wrote, “for the material and spiritual welfare of our boys in the camps; for the protecting hand of God in behalf of the soldiers and sailors on the sea; for the success of our armies and those of our Allies in their noble and strenuous efforts to defeat the forces of autocracy and cruel vandalism; for such liberality and sacrifice as shall result in the overwhelming subscription of our Fourth Liberty Loan; and for such speedy success in the war as shall mean a righteous and permanent peace on the earth.”

The pandemic claimed clergy lives. The Rev. R.B. Miller, pastor of Third Presbyterian Church, died along with his young son of pneumonia. The Rev. Charles Hipp of St. Ann Catholic Parish in Castle Shannon caught a fatal infection “during his sacramental administrations,” according to the Pittsburgh Catholic newspaper, calling him a “martyr to duty.”

In late October, Bishop Canevin offered the full force of Catholic Charities and the parishes of the diocese in fighting the epidemic. The city accepted, and after some initial miscommunication with the city, the Pittsburgh Catholic newspaper proclaimed by early November that “priests, sisters and lay workers ready and prepared to answer any and every call.”

A central dispatching system received reports of needs and sent word to about 40 relief stations set up by Catholics around the city.

The paper told of Sisters of Mercy helping an influenza-stricken “Hebrew family” in the Hill District, of the Vincentian Sisters offering a temporary home for South Side children whose mother died and father was hospitalized, of priests who ministered to multiple parishes as their colleagues fell ill.

The Jewish Criterion told of similar efforts by various Jewish charities, from financial relief to burials, aiding Jews and non-Jews. The nurses and other workers from the Irene Kauffman Settlement House, a precursor of the Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh, “have gone into hundreds of homes visited by disease and death and given help to the sick and cheer and comfort to the bereaved,” the Criterion wrote. Women prepared “broths and other nourishing foods” for the sick.

By early November, local officials were agitating to end the state’s restrictions on public gatherings. The Pittsburgh Council of Church’s vice president told the Pittsburgh Post he would support keeping churches closed to protect public health even though he didn’t think it necessary, as “people do not ordinarily go to church when they are sick; most people take the first excuse that offers itself to stay home from church.”

Soon the bans were lifted and an interfaith thanksgiving service was held at the end of November, with Catholic, Jewish and Protestant clergy giving thanks for victory in World War I.

Calvary Episcopal Church today sees its forebears’ actions during the pandemic as setting an enduring example of opening doors to those in need, said its rector, the Rev. Jonathon Jensen. The church has opened its large sanctuary for use by Tree of Life / Or L’Simcha Congregation for its holiday services since the fatal 2018 anti-Semitic attack on its congregants.

“When the Tree of Life synagogue was in need for their high holiday services, we offered our space to them,” Rev. Jensen said. “If the Pittsburgh community is need of our facilities as a temporary hospital, Calvary will offer the space.”