AFTER D-Day – The 59th (Newfoundland) Was There!

By Neil Earle

Nazi officers sign surrender agreement in tent of Field Marshal Montgomery (left) on May 4, 1945.

Nazi officers sign surrender agreement in tent of Field Marshal Montgomery (left) on May 4, 1945.June 6, 2019 marks 75 years after the most momentous military date in history.

Page 689 of my history textbook back in Carbonear, Newfoundland, Canada in 1961-62 showed Britain’s Field Marshall Montgomery dictating surrender terms to the defeated German army at Luneburg Heath near Hamburg. That was May 5, 1945, three days before the official marker – May 8, 1945 for Victory in Europe. Nazi officers sign surrender agreement in tent of Field Marshal Montgomery (left) on May 4, 1945.

In spite of the relentless reporting of Herb Wells in the 1960s, it never dawned on me as a young teen that Newfoundlanders – specifically the 59th (Newfoundland) Heavy Regiment of the Royal Artillery – had been in on this event. Most of our military attention in school was focused, rightly, on the regimental tragedy at Beaumont Hamel in World War One. But the 59th had been in on the defeat of Hitler’s armies across Northern Europe from D-Day in Normandy to the climactic ending over the Elbe and into Northwest Germany.

The boys and men who made up the Allied armies had their best years ahead of them. Many were there like Jack Oates of Crocker’s Cove because “there was nothing much to do” in their small towns and bays but also because they were part of what we called the British Empire. As such they were volunteers – Democracy on the march! Almost a strange concept in an era when Western nations often appear feckless and hesitant about military power – Canadians more than most. But the truth was that Newfoundland gunners were a vital part of the British Royal Artillery and had participated in nearly every major battle of that epic march to the Baltic.

It’s a story worth the retelling.

Sweet Days of Youth

A visit to the Canadian Legion Hall in Carbonear refreshes the memory. There is displayed memorabilia of the men who fought in Italy with the other Newfoundland artillery regiment, the 166th – a story covered in the Carbonear Compass of 2014. However, in a quiet corner a simple pasteboard plaque salutes Lt. Jack Lee, Gunner Jack Keneally, Gunner John Murphy, Privates James Clarke and Joe McGrath. All were with the 59th (Heavy) Regiment. A family picture in our house at Carbonear’s South Side confirms that Messrs Lee and Keneally were prior associates. They had been hockey players together for the Carbonear Caribous in the 1930s.

The deadly 155mm “Long Tom” was the basic gun used by the 59th Newfoundland Regiment Royal Artillery across northwestern Europe.

The deadly 155mm “Long Tom” was the basic gun used by the 59th Newfoundland Regiment Royal Artillery across northwestern Europe.According to my aunt Em, Jack Lee’s parents ran a hotel where the new Post Office now stands in Carbonear. He had enough money to run a motorcycle around the town, she remembers, while the devil-may-care Jack Keneally was known to us hockey players even in the Sixties from the chant “Shoot, Keneally! Shoot!” – a reference to Jack’s propensity to hold on to the puck a little too long.

Thus Keneally and Lee, young roustabouts not unlike Gerald Saunders of Glovertown who – according to Herb Wells – volunteered for the Royal Navy at age 16 but was stopped by his parents. After escaping the Knights of Columbus fire in St. John’s in 1942, Saunders saw action from Normandy to Hamburg. Three very human lives set amid the mightiest man-made catastrophe of all times. How typical of that unassuming group of young stalwarts who were proud to serve as a volunteer unit. That alone makes them part of what we now call the Greatest Generation.

The Fight for Caen

G.W.L. Nicholson’s definitive 1969 account, More Fighting Newfoundlanders, catalogues the 59th (Newfoundland) Heavy Regiment’s, “almost continuous action” across Northwest Europe. After almost four years of training in the use of the deadly 155mm “Long Tom” and 7.2” howitzers, the 59th was ready to come ashore the night of July 4/5 1944, almost a month after D-Day. They were attached to Montgomery’s 21st Army Group of British, Canadians and Poles and the battle was fierce already around the strategic city of Caen where the Newfoundlanders were quickly deployed.

Herein hangs a humorous tale, at least the more fascinating of the two accounts we have. The first Newfoundlander to get into France on D-Day did it by mistake. The loquacious Jack Finn, a cocky hockey player with the ace St. Bon’s team back in St. John’s, possessed a native boldness. This led him to speak up at a pre-invasion briefing of British airborne troops he had wandered into accidentally. Though a forward observation officer for artillery (spotter) his thick accent made him suspicious – was this an Irish informer? The story goes the Brits were forced to detain and take gunner Finn with them in the small hours of June 6, 1944. The first Newfoundlander in Normandy!

There by default, Finney eventually found his way back to the 59th which was by then firing heavily against the seven German tank divisions thrown against Monty’s 21st Army Group around Caen. These strategic attacks by the British forces are often misunderstood in the war histories. Monty was not slow and plodding. His ceaseless attacks were making it possible to set up the American breakout further south that eventually led to the capture of Paris.

“Always in Demand”

Thanks in part to their skill as truck drivers and their accuracy as gunners, the four batteries of the 59th would end up being attached to both British and Canadian units. Their energy was noted. A Daily News report quotes a British officer who stated the Newfoundlanders were “never satisfied, no matter how many targets are given them.”

They were in it to the hilt and Richard Brinston of Stephenville area remembers it as hard, exhausting work requiring a team of 8-12 men. Gun placement pits had to be dug, usually with pick and shovel. Debris had to be packed around the weapons to ensure a greater angle for effective firing and guarding against recoil. Camouflage netting was needed. Usually the fox holes were the only safety in the face of heavy German counterattacks. That July, 1944 gunners Lawlor and Maloney won British Empire medals for their work in saving 20 Battery’s number one guns in face of a major night attack by the Nazi air force. According to Nicolson’s account, 16 enemy bombs fell in a one-half acre space.

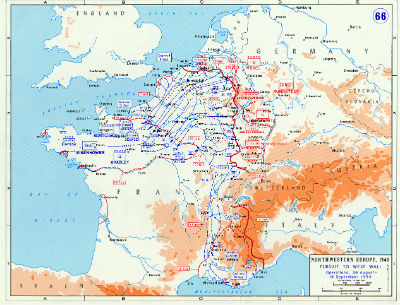

Normandy to Hamburg – the Newfoundland Regiment was part of Montgomery's 21st Army Group. Click map to enlarge.

Normandy to Hamburg – the Newfoundland Regiment was part of Montgomery's 21st Army Group. Click map to enlarge.“Cinderella on the Left”

But the Allied surge seemed irresistible. As the Germans fell back on Belgium, elements of the 59th helped cover the crucial Seine crossing. While the Americans liberated Paris and the British paraded through Brussels the Canadians were manfully pushing along the coast into Holland against heavy resistance. A key assignment? Eliminating Hitler’s V-2 flying bomb bases as they went. “Cinderella on the Left” the National Film Board later dubbed the often under-played Canadian effort. At least there was Antwerp. Newfoundland gunners enjoyed the wine and cigars passed out by the mayor of Antwerp in September even as the Allies failed to consolidate their gains on that great port city – tragically, as it turned out.

This was a crucial mistake. Antwerp was crucial to the entire Allied effort. Until the approaches to Antwerp could be cleared supply lines were being over-stretched all the way back to Normandy. The Second Canadian Corps were given the “formidable assignment” to assist in clearing a sixty mile water passage coming in from the North Sea. It would cement their reputation as dogged and determined warriors but at great cost.

The Newfoundlander gunners moved up in support. These waterborne assaults along both sides of the Scheldt Estuary featured some of the most heroic (and underreported) amphibious feats since D-Day. Day and night for five weeks, the 59th labored to drive trucks across wet farmland and spongy ground, doggedly erecting gun platforms amid soggy “polders” – Dutch soil earlier taken back from the sea. Nicholson describes “water-logged land…almost beyond credence that sites for heavy artillery could be found.”

Canada lost 3550 men in this epic five-week battle to clear the Scheldt. The Black Watch from Montreal was virtually wiped out and the North Nova Scotia Highlanders saw bitter fighting. The 59th was with them in support all the way. Their 155mm “Long Toms” could lob a 95 pound shell for 15 miles, crucial in covering the Canadian offensive. The native zest for life could not be suppressed. Somehow Lieutenant Jack Armitage of the old Guards hockey teams in St. John’s got his skates sent to the front. In the land of Hans Brinker the happy townie enjoyed many a leisurely skate in brief respites from war. An official press report praised the Newfoundland gunners’ at the Scheldt for their “superb job…one which the island may raise to a pinnacle of pride among the highest traditions of its history.” The Canadian Corps commander cited “the invaluable assistance of the big guns.”

Market Garden and the Bulge

Meanwhile another of Newfoundland’s four batteries had been in on the failed Market-Garden offensive, the “bridge too far” effort that September to leap-frog airborne troops across the Rhine and end the war by Christmas. The Newfoundlanders were given “numerous fires” around Nijmegen in relief of the Allied columns, turning their busy guns around three times in one day, reported researcher Alan Fraser.

Still there was growing elation: the Third Reich was getting closer. When Hitler launched his Ardennes offensive in mid-December, 1944 (the Battle of the Bulge) the four reunited batteries of the 59th Regiment stood ready to repel the German drive to the River Meuse, a key objective. The magnificent American defensive/counteroffensive action deflated the Bulge by late January while the Allies retreated (more or less) to winter quarters. And it was a cold one indeed.

It was at this time, as Fraser and Nicholson both relate, how British officers noted the “ability of the Newfoundlander to make himself comfortable in the most adverse circumstances.” “Boil ups” of spruce tea in the Dominion’s interior no doubt spurred the habit. It played out to good effect during that harsh winter of 1944-1945. Men from the 59th took cardboard from their shell casing boxes to make floors and sideboards for their small tents. They converted oil cans into miniature stoves and stacking empty milk-cans as makeshift chimneys. They did the best with what they had, townies and bay-men together.

“Bouncing the Rhine”

As 1945 dawned, the climax of the war in Europe approached. A cardinal task was “counter-battery fire” against dug-in enemy artillery and mortar and machine-gun nests. In January and February – often firing by night in the bitter winter cold – the Newfoundlanders supported the American Second Army in its move into Germany. Due to shortages of top-flight radio equipment there was an acute need for “spotter’s” to ferret out the best targets. Singled out for special praise at this dangerous activity were observers Monahan of St. John’s, Sullivan of Calvert and Riggs of Grand Bank.

On March 23, 1945 General Montgomery issued a directive to “cross the Rhine north of the Ruhr and secure a firm bridgehead and penetrate deeper into Germany.” The 59th was now supporting the 15th (Scottish) division. Forward observer Lieutenant Dermot Griffith went with them – the first Newfoundlander to cross the Rhine. The next day the gunners paused to witness the last massive parachute assault of the war – Operation Varsity. The casualties kept coming. The parents of a young French-Canadian lad killed in the assault later wrote to the Newfoundland chaplain: “I wish to thank you in the name of my family for having given my son the last duties of Christian charity. Everything you did for him was of inestimable value.”

Moments of Humanity

There was more work for Padre Farrell as the 59th made more than twenty hasty location shifts over the next 40 days as the war reached a crescendo. Padre Farrell celebrated an April 1 Easter mass at a busy crossroads joined by French, Polish, Dutch, Ukrainian, Russian and Italian prisoners, one Polish POW crying throughout, which touched Richard Brinston to the quick. “The music for the service, “reports Nicholson, “was that of tanks rumbling into Germany.” As the Canadians fanned North to deal with German pockets in Holland two Allied armies drove for the Elbe to beat the Russians to the Baltic and seal the Danish border. The Allied planners called up every 155-mm gun on hand to shelter the crossing of the swift-flowing Elbe River. The 59th was again in the thick of it to the bittersweet end.

On May 2 the Newfoundlanders made their last shoot – all four batteries, three rounds per gun – on Bergdorf an unlucky suburb of Hamburg. The next day Germany’s second-largest city surrendered and North Germany was secure, the key to the Allied wind-up.

For eight full weeks after V-E Day the 59th helped in the administration and rerouting of “displaced persons,” refugees of war. One Newfoundland soldier wrote back home that, “the weather is fine…Eggs are fairly plentiful and chicken and pork quite easy to obtain. We are living well.”

A typically modest and benign epitaph for what had been a remarkable and searing effort for all the Allies. The Newfoundlanders’ faith and good cheer consistently shone through. In an astonishing concession on his part, the American tank General George Patton later summarized: “I do not have to tell you who won the war. The artillery did.” And the 59th was there.

(Neil Earle is a history professor with Grace Communion Seminary and lectures on NL and her history.)