Source: The Good News (July, 1963), page 23.

Source: The Good News (July, 1963), page 23.“Good evening. This is Professor Reginald A. Fessenden speaking to you from Brant Rock, Massachusetts, at the tower of the National Electric Signaling Company. I’m going to play an Edison recording of Handel’s ‘Largo.’ Next I will play ‘O Holy Night’ on the violin followed by a short passage from the Bible.”

It was Christmas Eve, 1906. From his transmitter some 30 miles south of Boston, the brilliant and innovative Reginald Fessenden was launching the first recorded radio broadcast.1

It seems fitting that the first “broadcast” was a religious program. The word “broadcast” itself comes from the term English farmers used to sow their seedlings in a wide scattering motion. For the biblically-attuned, the tie-in with Jesus’ Parable of the Sower is enticing: “Behold, a sower went out to sow. And it happened, as he sowed, that some seed fell by the wayside” (Mark 4:3-4). Fessenden himself was the son of an Anglican minister from Quebec’s Eastern Townships. Christmas ideally lent itself to “O Holy Night” sung by a woman’s ghostly voice streaming down from the ether. The Scriptural reading was from Luke 2:9-14 which recorded the angel’s message to the shepherds outside Bethlehem announcing the message of “peace on earth” across the heavenly frequency.

Wireless operators offshore in the North Atlantic were shocked, entranced. Here was a woman’s voice beaming in on them through the airwaves. The very next week Fessenden’s New Year’s Eve program was apparently heard as far away as the West Indies. A powerful new medium was being born. Its value became strikingly apparent in 1912. That year the S.S. Titanic struck an iceberg off the southeast coast of Newfoundland. Her frantic wireless signals reached the S.S. Carpathia making possible the rescue of additional hundreds of passengers from the icy waters. Meanwhile, high atop his radio perch at the Wanamaker Building in New York City, a young David Sarnoff joined Marconi operatives in broadcasting news of the survivors to the papers, even if somewhat belatedly. Sarnoff, soon to head up RCA (Radio Corporation of America), was quick to see the possibilities of the new medium. The Marconi Company was not far behind. Within a week of the Titanic disaster, the U.S. Congress began hearings that led to compulsory wireless equipment installed on all American ships.2

Rapid development followed. What is not ordinarily known is that America’s churches were not far behind the bonanza!

On November 20, 1920, radio station KDKA, operating out of Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, broadcast live the political debate between President Warren G. Harding and Democratic challenger Cox. This event generated much public interest. Yet it was very soon after this – in January, 1921 – that KDKA broadcast the first-ever worship services from the sanctuary of Calvary Episcopal Church. By 1923, New York City alone was broadcasting three religious services each Sunday leading in 1924 to the Greater New York Federation of Churches initiation of its popular weekly broadcast, “The National Radio Pulpit.” This was over station WEAF which soon became WNBC.3 Churches and radio were early and dynamically linked. Already in 1923, Herbert Armstrong’s sometime healing collaborator, Aimee Semple McPherson, was broadcasting out of Los Angeles over station KFSG from a transmitter erected atop her newly-completed Angelus Temple. In 1926, Father Charles Coughlin (pronounced “Cog-lin”) began his dramatic radio career from Detroit, paving the way for Herbert Armstrong by inventing the persona of “the pastor as commentator.” In California, Charles Fuller, later to host the popular “Old Fashioned Revival Hour,” had made his broadcast debut in 1923. Soon M.R. De Haan’s “Radio Bible Class” could be tuned in from Grand Rapids, Michigan. These signals in the sky heralded the arrival of what has been considered “the most popular radio program in the history of religious broadcasting,” The Lutheran Hour.4

On October 2, 1930 from the studios of WHK in Cleveland, Ohio, with the Cleveland Bach Chorus providing the music, The Lutheran Hour’s Walter Maier offered forceful evangelical encouragement to families caught in the vise of the Great Depression. “But in the crises of life and in the pivotal hours of existence, only the Christian – having God and with Him the assurance that no one can successfully prevail against him – is able to carry the pressing burdens of sickness, death, financial reverses, family troubles, misfortunes of innumerable kinds and degrees, and yet to bear all this with the undaunted faith and Christian confidence that alone make life worth living.” After eight weeks, Walter Maier’s fervent preaching had generated more mail responses than the runaway radio sensation of the 1930’s, the comedy hit Amos’n’Andy. Religious broadcasting had come of age! At its peak, in 1989, The Lutheran Hour reached a listening audience of more than 20 million people.5

As Walter Maier’s nation-wide radio audience steadily grew in popularity, out in Los Angeles, in 1942, The Lutheran Hour’s future rival in terms of audience share, was just getting started. In April, 1942 listeners on the West Coast heard for the first time a new signature in the sky of radio evangelism. “The World Tomorrow! Herbert Armstrong analyzes today’s world news with the prophecies of…The World Tomorrow!”

Source: The Good News (July, 1963), page 23.

Source: The Good News (July, 1963), page 23.Angelenos and others up the West Coast and even listeners in Canada generously responded to the 1-2 punch of announcer Art Gilmore’s resonant baritone joined with radio preacher Herbert Armstrong’s unique mix of up-to-the minute news analysis with powerful preaching from the Bible.

It worked! HWA’s first two weeks of broadcasting over KMTR doubled all previous responses. As he would later record in his Autobiography:

I found the manager, Mr. Ken Tinkham, friendly…It was only a 1,000 watt station, but Mr. Tinkham explained how the transmitter was directly over an underground river, which had the rather freak effect of giving their signal a power equal to about 40,000 watts. Underground river or not, I found it true that the station then had a better signal than any station in Los Angeles, except the 50,000 watt stations. It was heard like a local station in San Diego, 120 miles away, and even in Bakersfield, which is over the mountains. 6

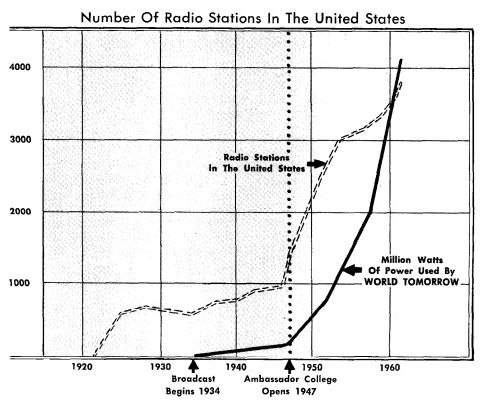

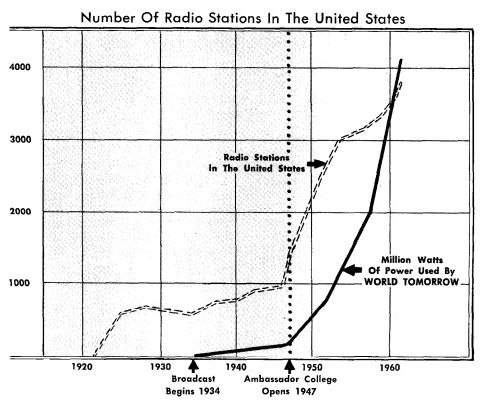

As luck would have it, the time was most opportune for HWA’s venture into news analysis in light of Bible prophecy. Marconi’s wireless invention and David Sarnoff’s exuberant promotion had pushed radio a long way by the 1930’s. In an article written for The Good News magazine in July, 1963, John E. Portune, an Ambassador College student at the time and an adept tinkerer/inventor in his own right, wrote about the fortuitous arrival of radio for the small Armstrong enterprise. Shorn of John Portune’s youthful exuberance, which advanced the claim that radio was the providential tool to enable HWA to fulfill Matthew 24:14, there is historical validity to his claim that radio was the pivotal shaper of what was, after all, “the Radio Church of God.” John Portune used reliable sources to good effect, sketching radio’s squawking infancy from the “obnoxious, howling black box in front of hardware stores.” Here is writer Ernest la Prade’s comments, for example, in Broadcasting News that “regardless when broadcasting began, its social importance could not begin to develop until there were listeners.”7

This seems obvious now but was not so at the time.

It was only in 1915 that David Sarnoff wrote to the Marconi Company about a “simple Radio Music Box...The box can be placed on a table in the parlor or living room…and the transmitted music be received perfectly within a radius of 25 to 50 miles. Within such a radius there reside hundreds of thousands of families.” And yet, as La Prade attested: “From 1920 to 1934 listeners…cared little what they heard, so long as they could identify the station that transmitted it.” The text Radio News Writing, cited by John Portune, gets to the heart of why Herbert Armstrong’s message would have such affect in the Los Angeles of the 1940’s. “In the period from 1934 through the Second World War radio news established itself to such a degree that the National Broadcasting Company, for instance, increased the total number of its news programs from 2.8 per cent…in 1937 to 20.4 per cent in 1944.”8

And what news there was!

By the 1930’s listeners were familiar with the stentorian announcer solemnly intoning “We take you now to London,” or “This is William L. Shirer reporting from Berlin.” H.V. Kaltenborn had delivered what was probably the first ever news commentary from Bedloe’s Island, New York over WVP. That was on April 14, 1922 from a station run by the Army Signal Corps and the subject at hand was a coal strike. A year later Kaltenborn was given a weekly series. By 1930 he was greeting fellow journalist Lowell Thomas as the latter passed him on his way out the door of the CBS studio in New York with, “You are the cocktail, I am the main course!” Big egos helped build big audiences. As Irving Fang summarized the development: “Adding a name to a disembodied but distinctive voice created a personality…Americans smiled when commentator Quincy Howe called those in his craft, ‘excess prophets.’” 9

The prophets had a ready audience. In far-off America, more radio sets were sold during the three weeks of the Munich Crisis September, 1938) than during any previous three-week period in the nation’s history. In 1939 nine million new sets were sold. By 1940, 81 percent of American families were listeners and “glued to the set” mean distinctly and distinctively radio!10 In this newly wired age, a time when an appeal from Father Coughlin could land 100,000 telegrams on a senator’s desk, an era when the President’s “fireside chats” delivered over radio offered competition to Messrs Kaltenborn, Thomas, Walter Winchell and Edward R. Murrow, the resonant, high pitched yet dignified tones of Herbert Armstrong could also cut through the clutter of soap ads, Burns and Allen sketches, and the Max Schemling-Joe Louis rematch. The war news charged HWA’s voice with a crackling urgency it would rarely lose. Here was his broadcast of August 22, 1940 for example:

And so, finally, let me give you one little bit of a comparison: Hitler’s plan of government will be National Socialism, but God’s plan is theocracy.

Hitler thinks the world will be ruled by the Aryan race of Germans; God says the saints will rule the world after they’re made immortal.

Hitler’s object is the enslavement of the world; God’s object is the liberation and freedom of the world.

And the only true Gospel is the Good News of the Kingdom of God, and I only wish I had more time to just go on and show you more of how this Kingdom is going to be ruled when Jesus comes. Just one little verse telling us who he’ll rule, the fourth verse of the eleventh chapter of Isaiah: ‘But with righteousness shall he judge the poor, and reprove with equity the meek of the earth: and he shall smite the earth with the word of his mouth and with the breath of his lips shall he slay the wicked.’”

“With the breath of his lips shall he slay the wicked.” This was a message that would preach to beleaguered, war-frightened, Depression-battered Americans honing in on their radio sets along the West Coast in the early 1940’s. Here was a man on the radio saying God was alive, that His word lived and that there was coming an intervention from the Almighty that would shut down the wicked monsters seemingly let loose upon the globe. “A breathless intensity” is the cliche most appropriate here to describe HWA’s rapid-fire dead-earnest delivery. At 150 words in 50 seconds for this particular rush of words, HWA was rivaling Kaltenborn himself who was usually rushing along at 150 words per minute for the first ten minutes of a half-hour commentary with gusts rising to 200 words per minute for his conclusion. (Walter Winchell took the records at 300 words per minute). What Irving Fang wrote of Kaltenborn could equally apply to HWA and explain much of his later style. “His enunciation was quite precise, thanks to self-discipline during the early years of radio when sloppy speech would not transmit clearly through poor microphones and equally poor radios.”11

What was also effective about HWA’s “controlled panic” mode of delivery (the phrase came from an astute British listener in the 1960’s) was his orderly arrangement and attention to the fine arts of argumentation. He had structure and he had obviously planned his talks. In the August 22, 1940 address he skillfully balanced his points with the alternating and rhythmic “Hitler plans/God plans.” The scriptures are read against that “beat the clock” urgency which was utterly unlike most religious proclamation. In short, he was prepared, even with his quasi-Kaltenborn tactic of speaking from 3x5 cards filled with notes, quotes and figures. Dale Salwak, a veteran speech instructor at Citrus College and an author in his own right, opened his evaluation of HWA’s above wartime address with a reference to that “crisp, clear articulation joined to a clarity of thought,” a clarity which “leaves no doubt that he believes what he is saying.” Professor Salwak adds: “There are no awkward pauses. There is an urgency in his voice which creates in us a desire to listen. There is a sense of the personal, his voice carries conviction with utmost clarity. There are echoes of Truman, Roosevelt, even Churchill in its urgency and tone. Above all it is a voice that carries a full, deep authority and enthusiasm.”12

Those evaluations would stay amazingly consistent over the five decades of broadcasting which lay ahead. Already, radio was proving the organizational lifeblood of what HWA called “the Work.” It was a vital source of recruitment as well as funds. This was already becoming evident by a letter Herbert Armstrong received from a listener in the Pacific Northwest, a bright young would-be artist for The Portland News. His name was Basil Wolverton and his letter to HWA began a friendship and association that lasted till Basil’s death in 1978. “Started listening to your broadcast in September, 1938, and since that time I have been coming to my senses,” Basil Wolverton wrote. “In other words, you have been the medium through whom God has acted to blast away my atheistic ideas, false conceptions and idiotic philosophies.”13 Basil Wolverton was not alone in his reactions. J. Harold Ellens’ analysis of the phenomenal popularity of the 1930’s radio priest, Father Coughlin, very much fit the Herbert Armstrong approach as well. “Coughlin was credible to the common man,” argued Ellens, “because of his appeal to simple logic. He started with the facts that bit into people’s lives, not with abstract theology.”14

HWA’s logic convinced Basil Wolverton. The young artist was baptized in 1941, ordained as an elder in the Oregon churches in 1943 and signed on as an early director of both the Radio Church of God and Ambassador College. “I wish you could reach a much larger audience and I’m praying for the time when you can,” Basil Wolverton would write. He also became instrumental in developing the “Bible Story for Children,” a Plain Truth serial through the 1950’s and 1960’s and became widely known to the membership for illustrating many later Worldwide Church of God productions, as well as his day job as contributor to Mad magazine and other popular productions.15

There were other incentives for HWA to carry on with the broadcast. A listener from Seattle wrote: “Received the copy of The Plain Truth a few days ago…I have wondered many times when these Scriptures would be revealed, and by whom, but God knew, and he has given the wisdom to one he can trust.” From Bingham, Washington, came this comment: “I thank God for men who can tell the truth about His plan of salvation. There are only too few in this time of great need.” A family from Deep River wrote poignantly but typically: I realize you do not ask for money, but I am enclosing $1 to help in God’s work.” Another subscriber added: “These certainly are the kind of Biblical explanations that the world needs today.” The words of a Portland, Oregon listener must have been music to the maverick radio preacher’s ears : “In your last broadcast you mentioned that the public might not approve your words…The Lord approves. That is enough.” Another eloquent Oregonian put his finger on the Armstrong appeal in those days of Biblical as well as world crisis. “This old world is now in the critical time when it needs a pilot to show us whether we are headed. You are doing a great job.” Another listener reflected the crisis of mainstream Christianity at the time. “I know you are giving the truth to those who…will not go to the present-day church and who hold the church to be a hypocritical racket. But they listen to you. Keep up the good work.”16

By the summer of 1942, then, Herbert Armstrong’s urgency and intensity were having their effects. From his base in Hollywood, he had to fulfill his radio commitments to Seattle, Portland and Eugene by mailing electrical acetate transcriptions of the broadcast from Burbank airport. Then KMTR’s owner hit him with an even bigger idea – daily broadcasting. It seemed that another religious broadcaster was rearranging his schedule leaving the 5:30 P.M. time slot in Los Angeles open Mondays through Saturdays, as well as 9:30 on Sunday morning. HWA was flabbergasted at the opportunity but definitely interested. Cost was, as always, the sticker. The new bill came to six times what the pygmy-sized Radio Church was already paying. Herbert phoned Loma in Eugene.

“Loma, quickly, how much money is in the church bank account?”

“Just enough for one week of the new schedule,” Loma answered. This time HWA gambled and took the offer!

The response was explosive! Even though the address given was Box 111 in Eugene up in faraway Oregon, requests for free literature boomed. Avid listeners sent in tithes and offerings enough to just cover the costs of the new expansion. Nip and tuck was the motto the next several weeks. HWA would receive just enough money each week to pay for the coming week’s broadcast, even as the size, scope and impact of his outreach was doubling. This seemed providential. He was relearning the lesson of the old rags and newspaper man when the family needed a dime for Ted’s milk. It was “Give us this day our daily bread.” Christians must be content. Slowly, the daily broadcast took root. “The World Tomorrow” was launched in good fashion in the City of the Angels. Southern California was proving fertile ground. It was a lesson HWA was heeding.

Would the city respond to Point 3 of his Three Point evangelistic strategy – public meetings?

Three months into the new “World Tomorrow” broadcast format Herbert Armstrong learned that the well-known Biltmore Theater, with seats for 1900 people, had become available for rental. The cost would be $175, he was told by a skeptical manager. Once again he checked with Loma in Eugene. There was just enough to cover that amount and the postal cards for a Los Angeles mailing. After announcing the meetings on the daily broadcasts, HWA, Dorothy and his 13-year-old son Dick who had sped down from Eugene to help out, were flabbergasted to see hundreds of people streaming to the Biltmore.

Where was the crowd going? Not to hear HWA?

Yes. Yes, indeed. They were coming to hear him. At precisely 3 P.M. at the Biltmore HWA strolled on his stage to intone his trademark, “Greetings, friends!” He spoke on the world war in the light of the prophecies. Some 1750 people heard that message. Then, true to his practice of “the Gospel going free,” he refrained from taking up an offering but announced that if anyone wanted to give a voluntarily donation to defray expenses that was up to them. Astonishingly, the content of the two offering boxes was one cent more than the exact amount needed to cover the theater rental, the janitor, electrical costs, signs and postcards. These were object lessons in working and living by faith.17

Thus encouraged, HWA engaged the next two Sundays at the Biltmore. He was met by some 1300-1400 people for each service. The Armstrong family-cum-evangelistic team were elated by these fulsome Angeleno turnouts. However, things definitely needed his attention back in the Northwest. HWA knew that his vital support base was still the churches of Oregon and Washington. Also, Eugene’s radio stations were not equipped to handle the complex transcription procedures needed for the burden of daily broadcasting. Thus, even though his first foray into the Southland had been auspicious, HWA moved to cancel KMTR. He did, however, add KFMB San Diego to his West Coast network before heading back to Eugene. Los Angeles would see a lot more of him in the years to come.

Returning to Oregon in 1942, Herbert Armstrong, soon responded to an offer from radio station KGA in Spokane, Washington. Working with station owners he patched together a “Liberty Network,” comprising KGA, KRSC Seattle, and the new outlet at KFMB-San Diego. Now, at last, Herbert Armstrong felt prepared to Herbert Armstrong felt at last ready to tackle giant WHO based in his home town of Des Moines, Iowa. Surely, coverage along the Pacific Coast would nearly double his income from new listeners. His uncle Frank, now retired but an influence in Iowa media circles, pulled the necessary strings to get him on nation-wide clear channel WHO for a mere $60 per broadcast, the local rate!

HWA was excited. At 11 P.M. Sunday night on August 30, 1942, Herbert Armstrong was back in his home town ready to address a national audience for the first time. Once again, Art Gilmore’s smooth baritone led the way. “The World Tomorrow! At this same time Sunday, Herbert W. Armstrong analyzes today’s world news, with the prophecies of The World Tomorrow!” Then came HWA’s impassioned opener: “Greetings friends! We enter the fourth year of this war next Tuesday. We entered the ninth week of the supreme crisis of the war today. In all probability the ultimate outcome is being determined right now on the Russian front.”18

This was a shrewd analysis of what actually was going to happen. The biggest battles were destined to be fought that fall and winter around Stalingrad after Hitler’s foolish foray into the Russian Caucasus area. His real subject however was Bible prophecy. He launched into his now trademark theme of an emerging United States of Europe which was tied to his interpretation of Revelation 17:12-14 which seems to point to ten actual kings destined to fight Jesus Christ at his return (Revelation 17:12-14). HWA estimated that Hitler would lose the war – perhaps by 1945, he later wrote in The Plain Truth. He next proceeded to speculate vociferously that Germany would rise again from the ashes and lead ten nations (the ten horns of Revelation 17) into World War Three. All this would set the stage for the return of Jesus Christ. In the context of the Allied life and death struggle in Russia and along the Pacific and Atlantic ocean fronts it was insightful and compelling. He offered also a rather bold intimation that the Allies would win the war, an outcome not at all certain in the dark year 1942.

The WHO experience would prove the source of one incident that must have re-convinced HWA of his sense of divine calling. He had to return to Studio and Artists recording store in Hollywood to make acetate discs suitable for replay over Des Moines super-powered station. One night, he admits, he came to the Hollywood studio bone tired. Even the recording engineer was displeased with the effort – the old HWA pep and energy was missing. Then the other-worldly dimension of radio intervened. The very night that inferior program went out over the air from WHO-Des Moines happened to be an extraordinarily cold night along the Great Plains. “In Iowa it was one of those 20-below-zero nights, without wind – cold and still,” HWA wrote later. “That is the kind of weather in which radio waves radiate with extraordinary sharpness.”

HWA’s dog-tired bass baritone crackled along the frequencies with a concentrated intensity. Radio’s “God-like” powers to surprise and startle were saving the broadcast. That inferior program drew 2200 responses. This, a grateful HWA remembered, was a total never equaled by any one “World Tomorrow” program until the late 1960’s.19 Saved – by the mysterious properties of the intimate medium. Herbert Armstrong would have to have been less than human not to feel that God was with him on such occasions.

1 Erik Barnouw, A Tower in Babel: A History of Broadcasting in the United States, Volume 1 – to 1933 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), page 26.

2 Tom Lewis, Empire of the Air, pages 105-107. Lewis is rightly skeptical of Sarnoff’s embellishment of his legend about certain events during and after the Titanic disaster.

3 J. Harold Ellens, Models of Religious Broadcasting (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974), pages 16-17.

4 J. Gordon Melton, Phillip Charles Lucas, Jon R. Stone, Prime-Time Religion: An Encyclopedia of Religious Broadcasting (Oryx Press, 1997), page 210.

5 Melton, Lucas and Stone, Prime–Time Religion, page 210.

6 Herbert W. Armstrong, “The Autobiography,” Plain Truth (January, 1962), page 14.

7 John E. Portune, “A Door God Opened – The Miracle of Radio,” The Good News (July, 1963), pages 3-4, 23-24. Most quotes that follow from this source. The Good News was the in-house magazine of the Radio/Worldwide Church of God at this time.

8 Quoted from W.F. Brooks, Radio News Writing (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1948).

9 Irving Fang, Those Radio Commentators, pages 4-5, viii.

10 Susan J. Douglas, Listening In, pages 161-162.

11 Irving Fang, page 30.

12 Dale Salwak, personal communication, May 28, 2006.

13 Klaus Rothe, “Artist’s pen leaves its mark on Church,” The Worldwide News (February 5, 1979), pages 10-11. The Worldwide News (WN) would serve as the church’s official news source from 1973 to 2004 and attract some of the WCG’s most talented writers and journalists.

14 Ellens, page 59.

15 Basil Woverton’s legacy is preserved by his son, Monte Wolverton, who is still with The Plain Truth magazine in its new incarnation (since 1996) as Plain Truth Ministries (PTM).

16 Letters cited in “The Autobiography,” Plain Truth (December, 1961), page 23.

17 HWA, “The Autobiography,” Plain Truth (February, 1962), pages 11-14.

18 HWA, “The Autobiography,” The Plain Truth (March, 1962), page 20.

19 HWA, “The Autobiography,” Plain Truth (March, 1962), pages 21, 45-46.