Keep Herod in Christmas

By Neil Earle

With God's help the wise men outflanked the murderous designs of King Herod. Shutterstock image.

With God's help the wise men outflanked the murderous designs of King Herod. Shutterstock image.Three years ago we members of the Glendora Ministerial Association met for our annual Christmas lunch in the center of town.

The Methodist pastor had been asked to give a short informal “sharing” on something appropriate to the season. As it turned out his message was about not ignoring the full aspect of the Christmas story, the wide and sobering affects of Jesus coming to this earth as the child of Bethlehem. In particular he cited the reference to what has been called “the slaughter of the innocents” in Matthew 2:16-18 when King Herod ordered the death of all baby boys in Bethlehem up to two years of age. This was his fiendish effort to exterminate rumors of a “King of the Jews” born in Bethlehem.

Atrocity then/Atrocity now

There are no historical records of such an assault but all scholars agree that Herod, who ruled Judaea under the Romans from 37-4 BC, was entirely capable of such an outrage. This murderous monarch slew three of his own sons as well as his wife, his mother-in-law and numerous members of his court, reported Tom Mueller in National Geographic (December, 2008).

For Christians this has always posed a theological problem: God’s son comes into the world and young baby boys die. How do we reconcile this with the Christian teaching on God’s sovereignty over this world?

Strangely, as we still absorb the press accounts of the massacre in San Bernardino just 40 miles from where I write there is a grim resonance between the Christmas story and its signature warm-hearted family spirit and the outrages in Bethlehem and in our own times.

We must remember that the people of Jesus’ day also lived in dark and dangerous times.

Insane rulers capable of great atrocities stalked and walked the earth in Jesus’ day as well (Luke 13:1).

Hair-trigger tensions were especially prevalent in First Century Judaea just as they are today (Romans 11:48).

There is one Christmas carol that doesn’t get much airing but sizes up the situation for the people among whom Jesus was born. It goes like this:

“O come O come Immanuel

And ransom captive Israel;

Who waits in lonely exile here,

Until the Son of God appear…”

The truth is that though the Roman world was enjoying the early decades of the great Roman peace that stretched from Spain to the Euphrates, Judaea was a province seething with resentment because of their recent loss of independence from Rome’s armies in 63 BC. The Herod family was notorious Roman puppets and the Gospels are full of this background tension. When Jesus said he who compels you to go one mile carrying his baggage, go two instead – this referred to a common Roman practice of forcing Jews to tow the line.

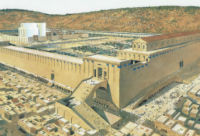

Artist's reconstruction: Even while Herod's magificient temple still stood God was building a spiritual temple through the humble lives of Joseph and Mary, Elizabeth and Zacharias (Luke 1). Click to enlarge.

Artist's reconstruction: Even while Herod's magificient temple still stood God was building a spiritual temple through the humble lives of Joseph and Mary, Elizabeth and Zacharias (Luke 1). Click to enlarge.Counteracting Mighty Rome

Now of course the Bethlehem story is full of the diametric opposite of this cold and ruthless and even murderous tension in and around Jerusalem, a city which Herod purposely adorned with marvelous building tor appease and impress the Jews who hated him (Luke 21:5-6).

The Gospel writer Luke in particular seems to go out of his way to project his account as a quiet deconstruction of all things great and powerful. He begins in the temple with John the Baptizer’s father, Zechariah, a humble priest serving out his appointed ritual (Luke 1:5). He and his wife lived in “the hill country” outside Jerusalem, away from the center of intrigue (v. 39). Mary lived in Nazareth a city of perhaps no more than 50 Jewish families and a place looked down upon. Mary’s husband Joseph was of the royal line but a carpenter, not a member of the professional classes. They were not wealthy, indicated by the fact that the pigeons they later offered in the temple were called the Offering of the Poor (2:24).

Luke, who coins the line “Blessed are the Poor,” gets all this down together with the famous declaration that “there was no room for them at the inn” when Mary became due. Jesus was placed in a manger, a crib for the sheep and oxen to partake of, but warm enough for a child born in the most humble circumstances, perhaps not a barn but an attachment of a house that was close to where the animals were fed.

Power and prestige enters the Bethlehem story with Luke’s introduction of the renowned emperor Augustus in Luke 2:1. The Romans held a census of their provinces every 12 years and this one sets things in motion that were to later gently oppose and eventually conquer the might of Rome. Three hundred years after Mary’s bumpy 80 mile journey to a manger in Bethlehem, a Roman emperor would adopt the Christian faith. Fifty years after that Christianity would become the official religion of the Roman Empire. Who’d have thought it?

Is it really true that the meek inherit the earth? Looks like it.

The True Light

But there was always of course the other side, the dark side and when people I know ask how they could ever celebrate Christmas this year in San Bernardino with the Biblical message of peace and light shining in darkness, then it is Herod’s atrocity that at least offers some perspective. It would ne unwise to leave Herod out of the Christmas story and overly sentimentalize these events recoded in the dying years of the last pagan millennium.

Jesus and his parents had to set out to Egypt as refugees for safe keeping till Herod was dead (Matthew 2:14). Here was an uprooting and an inconvenience that should speak to us this year when refugees have made the headlines. The reason to keep Herod in Christmas is to remind us that this is still a brutal and murderous world and darkness is all about us. But there is also the Light shinning in that darkness. Mary and Joseph making the rough 80 miles to Jerusalem were carrying that Light with them and Jesus told his disciples that his own followers were to be salt and light.

The lights that shine at Christmas remind us of our task and mission. While we wait for the final appearance in power of the Messiah from heaven we have to take heart, we have to do what we can to be bearing that light even against the dark specters of Herod and terrorism. For while there is evil and oppression all around at times, we mustn’t forget those members of the church in Charleston, South Carolina who refused to let their lights go out after a gunman slaughtered their own innocents. What shining Christian examples they were. With God helping us that light will burn brightly again in 2016.

A World Made Ready

When St. Paul looked back at the Bethlehem story he used a phrase that bespeaks God’s overall control of events – “when the fullness of the time had come” (Galatians 4:4 NAV). Various Christian teachers have followed the scholar Adolph Harnack’s lead in deciphering the fortuitous arrangement of events that made possible for Christianity to spread widely and rapidly in the imperial age.

First, the comparative unity of language and ideas made possible by Alexander the Great’s world-conquering march some years before. The Greek koine or common language allowed a common mode of expression to reach from Spain to the Euphrates.

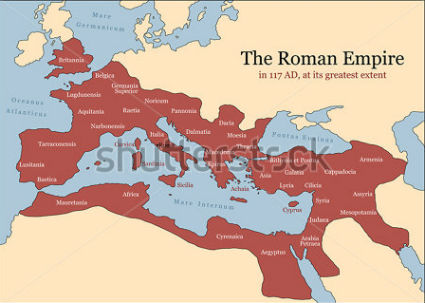

The mighty Roman Empire unwittingly prepared the world for the spread of the Gospel. Shutterstock image.

The mighty Roman Empire unwittingly prepared the world for the spread of the Gospel. Shutterstock image.The world-empire of Rome brought not only political unity but social cohesion to the lands under its sway. Just think, from the English Channel to the North African sands no one needed a passport or visa to get around a situation greatly aiding the command to “go and teach all nations.”

Third, the exceptional facilities favoring international trade, commerce and contact. Paul’s traversing the Mediterranean by sea in Acts 27 is an example. We still say “all roads lead to Rome” and those roads and those sea-routes were safe.

Next, a sense of humanity becoming one undergirded by a pervasive emphasis on Roman law and Roman citizenship. As the Romans extended the privilege of full citizenship to the provinces some sense of civil unity was spreading. Paul himself used his citizenship to further the Gospel (Acts 22:26-27). It was Roman governors who not only spared Paul’s life and allowed him free rein but one of those officials become converted on the island of Cyprus (Acts 13:12).

Fifth, the comparative equalizing of society and even the improvement in the lot of slaves. Romans still ruled the roost but the extension of Roman citizenship set trends in motion that furthered the prospects of a proselytizing movement moving out from an obscure corner of the empire. “The treatment of slaves became milder,” writes Harnack and some of them, such as Onesimus, made their way into Paul’s writings.

Sixth, Rome’s ad hoc policy of religious toleration which began two centuries before the birth of Jesus. The cult of Egyptian Isis was almost as popular in Rome as that of Jupiter which gave some “cover” to a new movement coming out of the East.

Seventh, the attractions of city life which led to city crowds able to gather quickly and giving the apostles a chance to build audiences almost immediately (Acts 3:11).

Eight: the rising vogue of a speculative and even mystical forms of religion especially those emanating from the East. Christian proclaimers of the resurrection were able to have their “flanks” covered in a society where religious discussion was rife.

Ninth, the spread of synagogues and small Jewish communities all across the empire. This gave the early apostles – especially Paul – a natural first place to start as First Century Jews were fervently expecting a Messiah (see Acts 13).

Tenth, the “portability” of Christianity if we can use such a phrase. The early Christians required no temples, elaborate rituals or brick and mortar institutions. They met in houses (Acts 12:12). This greatly aided the spreading of the faith – finding a river or stream for baptism would suffice, for example (Acts 8:36).

The field for receiving the good seed of the Gospel had indeed become well-cultivated by the First Century. The Almighty had his own purposes in Roman history, and all history.